Tea

What is tea?

Tea is a caffeinated beverage made by steeping the dried leaves of the Camellia sinensis plant in water. In the UK the tea is also used to refer to drinks brewed from other plants as well. The focus here will be on 'true' tea made from camellia sinensis.

There are two major varietals of tea plant used in commercial tea production:

- Camellia sinensis var sinensis

- Camellia sinensis var assamica

Camellia sinensis assamica is a large leafed varietal that favoured hot, humid climates. As such it is commonly found in Africa, India, Sri Lanka and southern Chinese provinces such as Yunnan and Guangdong. It is know for its bold, malty flavour.

Camellia sinensis sinensis is smaller leafed and more frost hardy. Found in Korea, Japan, Taiwan and Chinese provinces like Guangdong, Fujian and Anhui, it is known for producing teas with sweeter flavours reminiscent of stone fruit.

Hybrid and wild varieties of camellia sinensis also exist.

The Six Major Types of Tea

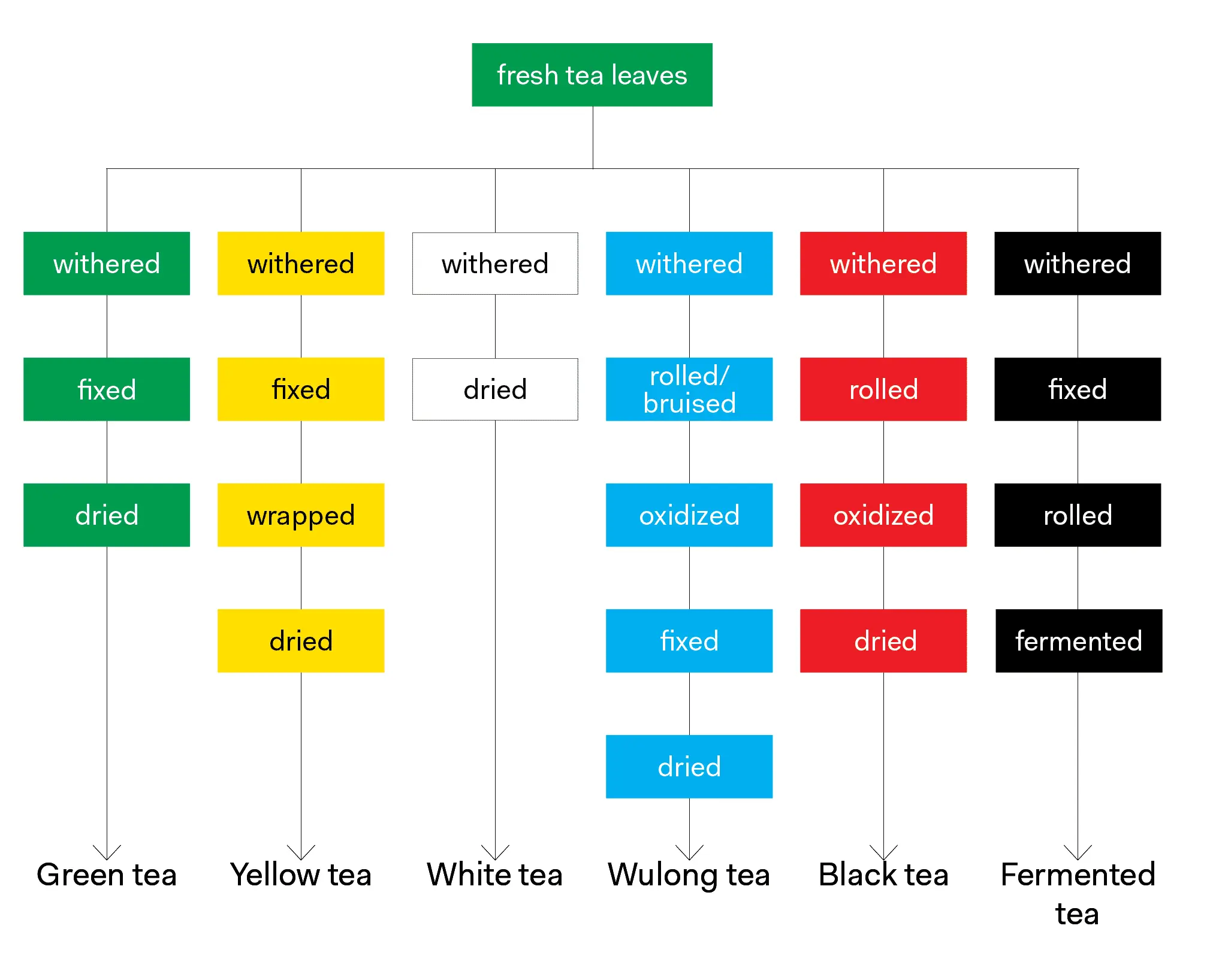

There are six major types of tea that primarily differ by levels of oxidation the leaves undergo. Other types of post-harvest processing also factor into the differentiation between the types.

These tea types can then be blended, decaffeinated or be flavoured, either through the use of artificial flavourings or natural flavourings such as oils, fruit or flowers.

This tea processing chart from teaepicure shows the minimum steps required to make each of the six major tea types. It should be noted that these steps often exist as a continuum rather than as discrete processes.

White tea

bai cha

White tea is fairly easily available in the UK, though you probably have to go to a specialist tea shop to find it. This tea is plucked, withered (often in the sun) and then dried without a heating step. This means that some oxidation can continue, changing the flavour of white tea slowly as it ages. White tea tends to be delicate in flavour with sweet floral notes. I quite enjoy white tea in the evening. Which might not be the best idea as, despite common wisdom, white tea often contains the most caffeine.

Green tea

lu cha

Green tea is also well known in the west, mostly for its vegatal taste and purported antioxidant properties. Very little is done to the leaves to make green tea; they're plucked, heated to stop oxidation and then dried. This is the type of tea I've struggled most with in the past. Bagged green tea has either been flavourless, too bitter and astringent or like drinking lawn clippings, with very little in between. I'm currently exploring Chinese loose leaf green teas and finding that there's more to green tea than I thought. Still haven't found a daily drinker in this category though.

Yellow tea

huang cha

Yellow tea is probably the least well known of the six major types, certainly in the west. It accounts for less than 1% of global tea production annually and can be difficult to find outside of China or Korea. Yellow tea is processed similarly to green tea, but has an extra step where it is wrapped in either paper or cloth. During this step the chlorophylls in the leaves start to break down giving rise to the yellow leaves that define this type. I've only tried the one yellow tea, and despite finishing a 25 g of it I still can't quite place the flavour of it. I definitely liked it though.

Oolong tea

wulong cha

Perhaps the broadest category of tea int terms of oxidation level.

Oolong tea is probably the broadest and most complex category of teas. They can range in oxidation level anywhere from around 20% to 70% and can be roasted or un-roasted. An unroasted, low oxidation ooling will taste completely different from a roasted highly oxidised one. There are four major oolong production areas: Taiwan, the Phoenix Mountains, Wuyi and Anxi, the latter three all in China. Each of these regions produces oolong teas with distinctive flavour profiles. Other regions have also started to produce oolong, but are less well known.

Red/Black Tea

hong cha

Called red tea (hong cha) in China, this is known in the West as black tea. This tea comprises of fully oxidised leaves and makes up 70-80% of global tea production.

Red tea is probably what you're most familiar with. In the west we call it black tea. We named it after the colour of the dried leaves, the Chinese named it after the colour of the drink it produces. Black tea is by far the most produced and consumed tea in the world, making up around 70-80% of global tea production. In the west, we tend to favour black teas made from the assamica varietal of the tea plant, which tends to have a bold, malty flavour which can stand up to the addition of milk and sugar. I've found I prefer black teas made from the sinensis variety; these teas tend to have a softer, sweeter flavour profile, often reminiscent of honey or stone fruit. I drink these teas unadulterated.

Dark tea

hei cha

Dark tea can sometimes be found in the UK, particularly puerh, though that is far from the only type of dark tea. Dark teas undergo fermentation of some sort after they are oxidised, either naturally occurring or intentionally done. The fermentation process again changes the flavours, often leading to earthier, woodier flavour profiles. In this category I've only tried puerh, and then I've only scratched the surface of what's available. When describing the last puerh I drank I said it tasted "musty, but in a good way." Yeah, this category isn't for everyone.

Altered tea

There's a seventh category of teas not present in the Chinese system, and that's altered teas. This is where something is done to alter the tea in some way after one of the traditional processing methods is complete. Think Earl Grey, decaffeinated tea, lapsang souchong. They're all altered teas. You could probably consider a blend like English Breakfast to be altered teas as well.

See Tea for reviews of teas I've tried.

Source: Tea: A User's Guide by Tony Webely

Planted: Sunday, 21 July 2024

Last tended: Monday, 23 June 2025